Electrohydraulic or hydroelectric? It’s odd how similar those two compound words are, yet they’re obviously entirely different in meaning. Hydroelectric refers to the production of electricity by way of converting the potential kinetic energy found in conjoined bodies of water of varying height, into electrical energy used by everyone and their hamster. Electrohydraulic is the term used to define the electrical or electronic control of hydraulic components, such as solenoid valves, proportional valves or electro-proportional pump control.

The world of fluid power appears to be behind the rest of the world by about two decades, by my reckoning. The industry is still transitioning from manual analog control (good ol’ hand levers) to electronic control. The transition is underway, and reminds me of the same advancement that occurred in everyday passenger cars … in the 1980s! Sure, Industry 4.0 is supposedly upon us, but the smart factory is still in its infancy.

The proliferation of electronics in the 80s allowed us to eschew old school “technologies” such as points ignition and carburetion for electronic fuel injection and ignition. Electronic control was more accurate, responsive, efficient, and reliable compared to the use of mechanical gadgets supplying the engine with fuel and then “blowing it up real good” with a nice spark.

We live in a capitalistic society where the markets make important decisions on our behalf, only some of which are related to engineered and manufactured products for our use or consumption. The market (with some political spinning from the government) forced the world to adopt electronics, and there are few persons who would admit we’re not better off because of it. So why has the hydraulic industry taken so long to come on board? The short answer is, “I don’t know.”

The good news is, we’re coming on (circuit) board. Electronic control of fluid power is as big as it’s ever been, and only getting larger. Much of our industry, especially in industrial applications, already uses electrohydraulics or at least electrical control of hydraulics. With an all-electrically controlled machine, the hydraulic components can be placed in strategic locations to improve machine responsiveness as well as decrease installation time (it’s easier to run 50 ft of electrical wire than it is to run 50 ft of hydraulic hose). I know you Millennials reading this on your iPhone are stupefied that I’m even discussing electromechanical technology, let alone manual control, but it’s a reflection of our industry.

Even if you have 30 sensors and valves on a machine now, a CAN Bus network will require just four wires to run around the machine, rather than hundreds. These systems lower installation costs even further, although each “station” requires its own microprocessor. Thankfully the cost of electronics is at commodity level prices, so that doesn’t cause much of a problem. Going even further, wireless smart devices communicate with each other or PLCs to provide real-time data on machine performance, cycle times, pressure, flow, or even wear rates.

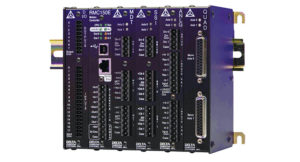

Even in industrial applications where electrical control of fluid power has been the standard for 30 years, the current renaissance is in how the hydraulics is controlled. Instead of push buttons, relays and/or contactors, we now have solid state microprocessors with feedback inputs as well as switched and proportional outputs, all tied together wirelessly (at least from a communication perspective). Essentially, PLCs can now be purchased for only a few hundred dollars, and hydraulic or pneumatic machines can be fully automated via an app on your computer or another device.

Electronic control cabinets that used to cost tens of thousands of dollars can now be replaced by a fist-sized controller with a dozen sensors giving feedback on machine parameters. More good news is that these machine controllers are flooding the mobile equipment market. My claim that the fluid power industry is 20 years behind in technology was mostly targeted at the smaller mobile OEMs, who are still having trouble giving up manual control of hydraulic valves, even when they’re already electrically controlled.

I suppose having a manual backup makes you feel secure in your Snuggie, but apart from that, electronic controllers can give the mobile machine the same advantages seen in industrial manufacturing plants. Electronic motion control and automation are possible with rugged and versatile machine controllers, which are just like PLCs. Instead of using a standard flow control valve, your proportional directional valve can control actuator speed as well as direction.

Industrial users are saying, “So what? Servo and proportional valves have been doing that for years!” Sure they have; but now that you can buy proportional valves for a hundred bucks and change, mobile OEMs now have solutions for cost-sensitive machines like wood chippers, log splitters or portable conveyors. On top of that, with electronic feedback, these machines can be more effective and productive than ever.

If you have a conveyor, simply add a speed sensor to send a signal back to the controller, which in turn varies the proportional valve providing the required flow for the chosen conveyor speed. The conveyor is now stable at the set speed regardless of fluid temperature or viscosity, or of differing load changes; the PLC only cares how fast the conveyor is going and adjusts the valve to maintain speed.

The reliability of electronics is outstanding. Consider how many smartphones are on the market, but also consider how many have had electronic failures not related to being dropped or stepped on. There have been advancements related to electrical control of hydraulic components, too. Solenoid valve coils, for example, can handle abuse seen in extreme applications like salt spreader trucks or offshore energy applications.

Simple electronic control of fluid power will slowly transition into a data managed world; a world allowing your Fitbit to control the temperature of your house to improve your sleep. However, we’re not there yet, and it’s not coming as quickly as you think, no matter how many conference keynotes you see presented on the topic. A Tesla travelling at freeway speed still can’t prevent itself from hitting a stopped car, and farmers don’t want to control their log splitter from their Apple Watch. Personally, I’ll be the guy lined up to buy the last manual transmission car on the market, which could be the 2043 Mazda Miata.