By Josh Cosford, Contributing Editor

When well cared for, hydraulic cylinders should last decades. So long as they were designed for their application — meaning they perform within the bounds of their environment — there should be no reason for damage or wear outside of regular use. The mount, rod and raw material should have been selected to best suit the cylinder’s purpose. If your machine was not so lucky to have been designed by a thoughtful engineer, ask yourself if constant failures are the result.

The steel and synthetic rubber construction of hydraulic cylinders make them highly durable. The head, cap, flanges and mounting fixtures are all made from steel. The piston rods use high tensile chromed steel, while the tie-rods use elastic steel trademarked as Stressproof that is both strong and elastic. Finally, the “wear” components must be alternate metals to prevent galling, so bronze and cast iron make the top choices for bearings and pistons, respectively.

We select the above materials for their strength and durability. So long as you respect your cylinder by protecting it from physical damage during operation, the cylinder should enjoy nearly infinite life. Every individual piece of a hydraulic cylinder is replaceable, especially when you work with an experienced and qualified hydraulic shop.

When to repair

Some exceptions to infinite repairability do exist, however. Just like your vehicle, sometimes the cost of repair warrants an entirely new cylinder. Your off-the-shelf “farm” duty cylinders may cost more for a technician to inspect, let alone replace. Also, some larger implement cylinders with welded bodies may only make sense to repair the gland, rod and piston assemblies. Should the barrel with its welded mount fail catastrophically, it’s best to replace the entire cylinder.

A high-quality NFPA, mill-type or high-quality custom cylinder almost always warrants a repair. The comparison to a new car is valid since I often find myself looking at a cylinder imagining the car I could purchase with the same dollar value. With the car comparison in mind, it almost always makes sense to repair rather than replace.

So many local hydraulic shops make their ends meet from repairing cylinders, so you get the idea just how repairable they are. NFPA and mill-type especially were designed with repair in mind. NFPA cylinders employ square caps spanned and fixed to a barrel using tie rods. These tie-rods are threaded into the cap or head, typically on one side only, while the opposing side gets torqued down with a high-strength nut. Removing the nuts and tie rods makes quick work of cylinder repair because the entire assembly easily (usually) comes apart.

Mill-type cylinders enjoy the same level of repairability, except for different reasons. Rather than tie-rods compressing the cylinder assembly, a mill-type cylinder uses flanges welded to either end of a heavy-duty barrel and the head and cap bolt to the flanges. Mill cylinders may be more complicated than my simple explanation, but the takeaway is their repairability equals NFPA cylinders. In fact, mill-type cylinders may be repaired will still fully or partially installed in the machine.

Common repair procedures

Regardless of the type of cylinder in for repair, hydraulic shops operate using similar procedures to diagnose, quote, and then repair your cylinder. Upon arrival at the repair facility, the first step is to log the cylinder into the shop’s ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) software and then provide a visual method of identifying the cylinder as it moves through the repair process. It helps when you provide as much information to the shop as possible, including the machine number, the cylinder function, and perhaps references to previous repairs.

After entry into the ERP system, Trulinx by Tribute, for example, a work order or shop job is created to identify the unique line item for this cylinder and the relevant customer. The customer and job information may be printed on a traveller attached to a clipboard that follows the cylinder in the various repair stages. At the very least, a manila wire tag with the same relevant information works just as well.

Using the relevant cause of failure information written on the work order, if it exists, the technician working on the repair starts with a visual inspection of the cylinder. They’re looking for apparent physical damage, such as a bent rod, broken threads, damaged tie-rods or anything other obvious sign to start their diagnosis. A bent rod, for example, requires a unique approach to repair. A bent rod prevents removing the gland or bearing assembly, so the head must be disconnected from the barrel assembly allowing the technician to pull the entire piston-rod assembly out. The piston must be removed to allow the bearing-containing head to slide back off the rod.

If no such apparent damage exists, the technician rightfully assumes the problem stems internally. Most cases of cylinder repair require just the replacement of seals if you’re lucky. The next step is disassembly, where the technician removes and inspects each component of the cylinder. What the technician sees from the disassembly process often helps with the diagnoses of machine problems well.

Common failure points

Should the flat, metal, inside surface of the cap look like it was pounded upon by a ball-peen hammer, the technician rightfully concludes a large chunk of contamination worked its way into the cylinder and was hammered upon repeatedly by the piston. Should the pounding marks find themselves on the cap, the opposing piston surface will share the same damage. These troubleshooting observations allow the technician to pass along critical information regarding the health of their hydraulic system. I’ve seen a steel nut that had somehow made its way into the cylinder, so these occurrences are not so rare as I’d hope.

More often than not, the technician will find the seals simply worn out. The worn seals allow fluid to pass, reducing both the maximum force and flow the cylinder can achieve while fluid bypasses the piston. Occasionally the end-seals will have failed, which is the case when the tie-rods stretch because of over-pressurization, subsequently nibbling some seals through the extrusion gap. Seal failure may be typical wear or catastrophic, such as when the piston seals melt when exposed to extreme ambient heat. Regardless, simple seal replacement is the best-case option for cylinder repair.

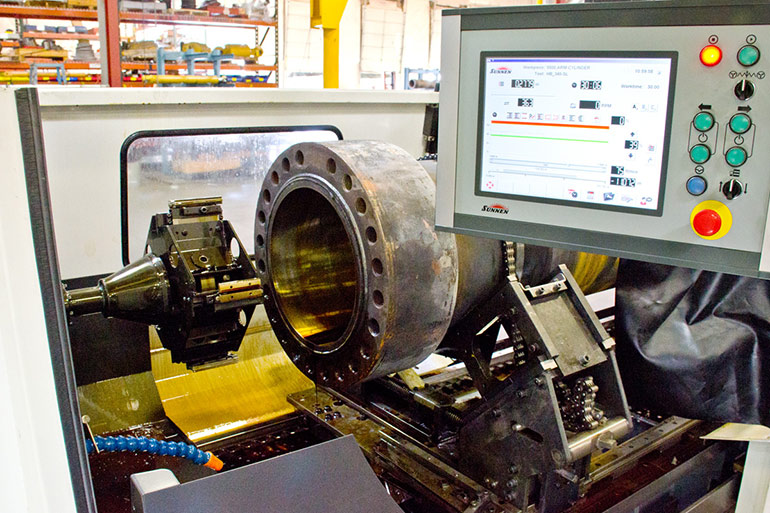

Other common problems found upon opening a cylinder are rod, barrel or piston wear. Applications experiencing side load result in accelerated wear on opposing sides of the bearing and barrel, respectively. For example, side load may cause wear on the bottom of the barrel in conjunction with the bearing’s top. Replacing the bearing and honing the barrel is required for these failures, and of course, I recommend you replace the seals every time you open up the cylinder.

Other less common cylinder failures include rod thread breakage, stripped fluid port threads, stretched/broken tie-rods, rust or corrosion, and stripped piston threads. A massive challenge for any North American repair shop comes when working on metric designs. Sourcing metric rod and tube raw material especially make repair difficult. In the end, a custom-turned and honed barrel may be required to finish a repair. Further still, a rod machined from cold-rolled steel to match metric dimensions will need to be sent for chroming, adding cost and time to the project.

Some repairs may be downright bizarre and seem to manifest when customers attempt a repair themselves. It’s not unheard of for a customer to simply butt-weld a broken rod end right back to the end of the rod. These “repairs” highlight the lack of trained technicians working in the field since they’re unaware of the tight clearances between a piston rod and its complementary bearing and rod seals. A butt-welded rod will shred the gland assembly nearly as fast as the rod broke the first time.

Know what to expect

Regardless of the failure, the technician must log not only the estimated time required to repair the cylinder but a list of the components required for refurbishment. New seals, rod or piston, are the three most commonly replaced items during repair, although literally, every component is fair game should they need replacement. The list of replacements then returns to the person(s) charged with creating a Bill of Materials in the ERP software, and then that person compiles the part numbers and prices into the BOM.

High-quality ERP software expedites the quoting process by automatically generating Requests for Quotes to their respective seal or raw material supplier. Still, a phone call or email works as well. When the supplier provides the price and lead time of the repair components, the desired profit margin (price markup) adds to the costing.

The customer’s repair quote offers both price and lead time, at which point the customer may decide to either repair, replace or scrap the cylinder altogether. Larger cylinders make more economic sense when it comes to repairing, while you may scrap smaller cylinders more often. Regardless, you leave the decision in the customer’s hands.

Should the customer decide on the repair option, the work put into diagnosing and quoting the cylinder makes short work of the process. The purchasing department orders the required material (if it’s not already in stock), and upon arrival, the replacement parts and seals are placed alongside the repair in its staged location. If the repair requires machined parts, these may be done in-house on manual or CNC machines or perhaps outsourced should the repair shop not have the machinery in house.

When all ordered and manufactured parts are ready, the technician may assemble the cylinder after a thorough cleaning and prepping of the individual parts. The assembly should be no different from a new cylinder, starting with the piston-rod assembly, then inserted into the barrel before being capped and buttoned-down.

No cylinder is completed until it is tested to the customer’s specifications. The test procedure may require specific measurements, leakage or pressure tests. Either way, a hydraulic cylinder should perform just as well as new. In fact, most repair shops offer the same one-year warranty that manufacturers offer when new.

Once the testing is complete and passes to the customer’s requirement, it may be re-painted if the customer requests such. As far as I’m concerned, the repair isn’t complete until it’s running again on the customer’s machine, where any errors in the repair process expose themselves. So long as the customer continues to respect the cylinder, it’s now ready for years more service life.