Understanding what can go wrong ensures that hydraulic pumps get built right.

Every OEM says it wants quality, but the reality is that machine builders can choose from countless hydraulic components that vary widely in performance and price—from cheap, “throw-away” parts to high-quality and, more-expensive, products that are built to last.

How does an engineer sort out the various offerings? Here’s a look at one fluid-power manufacturer’s unique philosophy on making a well-crafted pump, thanks to a keen understanding of how poorly built pumps fail.

Mechanic mindset

Most pump designers begin with theoretical concepts of fluid power and mechanical engineering to create a product that should suit the customer’s needs. Hydraulics manufacturer Permco Inc., based in Streetsboro, Ohio, has taken a different tack on the route to building high-quality parts.

Permco’s roots began in the early 20th century as a small shop servicing Appalachian mining equipment. “Unlike most traditional manufacturers, we got our start in this industry on the repair side. We had the chance to start at the opposite end of the learning curve—with failures—and looked at all the things that could possibly go wrong,” said Robby Shell, the company’s chief operating officer.

It’s hard to imagine worse operating conditions for hydraulics than in underground coal mines, he explained. Mechanics routinely dealt with units with internal parts burned due to overheating, seized from lack of lubrication, fouled with contaminants or damaged due to overpressure conditions. They also learned firsthand a sense of urgency to make a repair right the first time and get machines up and running quickly, as the cost of unexpected breakdowns can run into the tens of thousands of dollars an hour.

“So from that rebuild failure analysis experience, we got to see what impact engineering design, manufacturing processes and quality control, as well as operating conditions and servicing, played on the overall performance and life of components,” Shell continued.

“By virtue of our background, we got to see what worked and didn’t work, and what failed under normal circumstances. Therefore, when we started to manufacture these parts, we had the benefit of touching thousands of failed units before we ever made our first new one,” said Shell.

Manufacturing edge

“Take our gear pumps. We looked at many designs and the best gear design, based on our experience in differentials and transmissions for these applications, has a gear tooth that is shaped vertically, and then shaved after the shaping process,” he said.

Why? Well, cutting a gear tooth vertically produces little tiny cut marks, he indicated. Left as is, those imperfections would grind against each other, generate noise and wear debris, and hurt efficiency. A post-machining shaving process, however, removes the marks and smooths the face for quiet operations, and it also ensures parallel contact between the housing and gear profile.

In contrast, virtually every other competitor cuts their gears on horizontal hobbing machines, said Shell. “Just by the nature of a hobbing tool, those gears will have a crowned profile from end to end. When new, the difference isn’t noticeable.” But over time, as the gears rotate against each other and the housing, a crowned gear creates leak paths. Pumps with vertically cut gears, in contrast, have a straighter tooth profile and wear more uniformly, and thus maintain efficiencies longer, he said. “We were gear cutters in the old days, and that background taught us to implement design features that enhance the operation of our pumps. The way we shape and shave our gears creates a better tooth profile.”

Beware of copycats

Some hydraulics manufacturers rely on their own foundries and pour their own housing castings. “Well, in the foundry world, technology is really, really expensive. Upgrades are very costly, so there is a natural reluctance against constantly investing in the newest systems,” noted Shell.

Companies like Permco aren’t boxed in. They have the luxury of choosing foundries that rely on the latest and best technology. Not only are there cosmetic differences between state-of-the-art castings versus older offerings. It also results in higher density and fewer porosity issues, which translate into better mechanical integrity and machinability.

Another differentiator among pump manufacturers, in Shell’s view, is that some make high-quality, well-engineered products, and others either don’t understand the basics or simply don’t care.

“For instance, some years ago Permco developed a game-changing thrust plate called a diverter plate,” he said. When subjected to system pressure, the gears in a pump tend to flex and move toward the low-pressure side. To compensate, company engineers developed thrust plates incorporating precision grooves that create a minute flow path to divert high-pressure fluid to the inlet side. In turn, that helps balance bearing loads.

When the patents expired some competitors copied the plates and, without understanding why the feature is there, went one step further and introduced a bi-rotational version—with flow paths in both directions for running a pump clockwise and counterclockwise. They surmised that if the diverter works in one direction, a design suited for both directions would be even better. In reality, the bi-ro design doesn’t work because it creates too many leak paths and efficiency drops severely. But unsophisticated pump builders don’t know that. “We see a lot of those types of issues. They don’t understand the nuances of what this groove really does. They know it has 14° a chamfer on it. Why 14° not 16°? They can’t tell you those things,” said Shell.

Assembly and testing

Not only do such differences matter in design and manufacturing, they hold for how pumps are assembled, too. Building a high-quality pump is meticulous work, stressed Shell. “Our people do prep work very similar to what you would see in a good engine rebuild shop.” For instance, they might take a honing stone or emery cloth and kiss a few areas on the gear before installation. That’s because when gears are pulled from a warehouse shelf and moved to the assembly station, it’s not unheard of to accidentally bump and nick a gear. If that gear gets assembled as is, and it subsequently rides on the soft bronze plate, the burr will cut a groove and create a leak path. Left unchecked, that pump will run inefficiently and underperform. Few manufacturers take such a hands-on approach to quality, emphasized Shell.

“But probably the biggest thing that differentiates us is we test every pump that goes out of this building. For peace of mind from the customer’s standpoint, that’s huge,” he stressed. Each pump gets assembled with new parts to create a tight package. Then it’s run up to 2,000 psi pressure, where the components flex and the gears will take a take a slight wipe—removing perhaps 0.0005 to 0.001 in. of material from the housing. That’s acceptable, notes Shell, because filters on the test benches trap the wear particles, instead of remaining behind to contaminate a customer’s hydraulic system.

Tests confirm leak-free and quiet operation and that flow meets design specs. And any problem gets flagged immediately, not at the customer’s site. It’s a significant undertaking. That’s why most other manufacturers only test 1 in 10 or 1 in 50 units, said Shell.

Finally, the approved product is assigned a serial number that includes the initials of the assembler—as a further sign of the workmanship that stands behind a high-quality pump.

Stressing quality

“I guarantee you many other manufacturers don’t take the extra care we put into these units,” said Shell, and it shows when they test competing products. “Some of the dump-truck pumps coming in from offshore sources—mainly China—have failure rates upwards of 10 to 15%. Ours is less than one quarter of 1%.”

It’s due to a different mindset behind the way they build pumps, versus Permco’s philosophy, he emphasized. Some manufacturers feel units made to less-stringent standards are acceptable because often, they only see light duty. Take the case of a typical dump truck: the duty cycle for the hydraulics is often quite limited, he noted. Generally, a truck gets loaded, transports material to a site, and only then is the pump switched on—where it operates for perhaps a minute to raise, dump and lower the bed. And the cycle might get repeated perhaps a dozen times per day.

So, in theory, a dump pump designed and built to handle just light, intermittent duty should be more than adequate, he continued. But the world isn’t perfect—many things can and will go wrong, said Shell. For instance, the operator keeps the pump on too long and it overheats; or it runs low on oil; or the truck bed is overloaded, and a pump with no margin of safety is overtaxed and fails.

A well-engineered, high-quality pump can overcome many of these issues; lesser products can’t, he said. “We understand how offshore units are built and we can predict, generally speaking, how they will fail.” Almost all of these areas of weakness get addressed in Permco’s engineering, manufacturing, assembly and testing processes—steps that are missing in pumps coming from offshore sources. But those manufacturers justify an increased failure rate because their pump costs $50 less to make, said Shell.

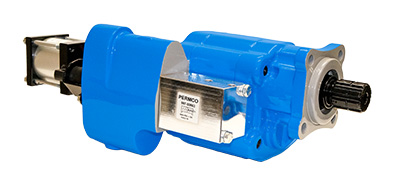

“We saw the invasion of these offshore dump pumps a few years ago, and we had plenty of opportunity to make this same pump in China. So we had two choices in that market. Either join it, and it’s just a race to the bottom. Or offer something that differentiates us from the rest of the market.” That’s where the American Champ, Permco’s pumps like the Gemini series comes in, he explained.

The pumps are engineered and manufactured based on Permco’s years of experience, and assembled in the U.S. from globally sourced, world-class components. What’s interesting is that many of the pump components are made not only in the company’s Ohio plant, but in Permco’s manufacturing operation in Tianjin, China.

“There’s virtually zero difference between our China and U.S. products, and there’s a reason for that,” explained Shell. Instead of relying on subcontractors or joint ventures, 16 years ago the U.S. plant manager (now with 44 years of experience) moved to China to set up a gear manufacturing plant, with processes identical to those in the domestic plant. By installing the same types of machine tools, instituting the same procedures, and with in-depth training and constant supervision, the Chinese workers have come to understand how important quality really is.

“It’s all about a different way of thinking. Again, we came out of the mining component repair world. When a Joy mining machine breaks down and sits idle for 16 hours, and a rebuilt transmission gets carted six miles underground to make the repair, it is imperative that when power is switched on, the work was done right.” The focus is on getting the equipment up and running again, not on saving a few dollars on a pump that might fail in short order, or may not work at all.

Hydraulic dump pump sees double duty

Dump pumps, as the name indicates, are routinely used in hydraulic circuits for lifting and lowering dump truck and trailer beds. The basic design typically includes a pump section, a directional control valve and a relief valve incorporated into the pump as a complete package, with internal fluid connections to the components. They have been around for more than 50 years and are common throughout the industry.

A notable innovation is now shaking up that market. Permco has developed a unit that sets it apart from conventional dump pumps. The Gemini DG-20/RG-20 is designed for-dual use applications, thanks to a second set of relief valves and selector valves. That lets the Gemini not only control a dump bed, it can also control a walking (live) floor.

Walking floors are used on trailers that do not tip, like a dump trailer. Instead, slats on the movable floor transport and “walk” the load off the end. They’re frequently used in the refuse industry, in landscaping to handle mulch and wood chips, and in other areas where height restrictions would severely limit the capability to raise a dump bed.

Walking-floor trailers tend to operate at higher pressures than hydraulics in dump applications. Traditionally, that has meant a fleet operator with dump trucks requires separate tractors for walking floors. Now, thanks to the Gemini pump, an operator can run a dump truck, and then switch the same tractor to a trailer with a walking floor. Equipping the vehicle with a Gemini pump system lets the operator easily change pressure settings on demand, and eliminates the need for a dedicated rig that can easily cost $150,000.

Another notable engineering feature is that the Gemini also incorporates a load check feature into the valve design, letting the operator raise the bed and then hold the load in place—say when spreading asphalt. To enhance reliability, the design differs from conventional units in that it’s direct-acting.

Typical designs incorporate a load check into a pilot-operated relief valve. As a result, the tiny orifice pilot senses operating pressure before it activates, but the orifice can easily get plugged by contaminants and the valve fails. The Permco direct-acting relief valve eliminates orifice plugging issues.

The load check and relief are also self-cleaning. Because it mounts in the flow stream, and clearances are sufficiently large, contaminants are flushed away—so there are few occurrences where the relief valve can’t open or close and a bed drifts or hangs up. That, according to Permco officials, offers a distinct advantage over competing designs.

The Gemini is rated for 37 gpm at 1,800 gpm and runs at two pressures, low (2,000 psi) for dump bodies and high (typically 3,200 psi) for live floors. Operators can easily switch from low to high pressure using cab-mounted controls. The pump includes dowelled construction and is assembled in the U.S. and 100% factory tested. In addition to use on dump trailers and walking floors, the Gemini is also suitable for gooseneck transporters, dump trucks, crane-equipment vehicles, roll-off trucks and refuse collection

applications.