Hydraulics can be overlooked by system designers looking for precise motion. However, by selecting the right components, the result can be a high-precision, high-performance motion control system at a reasonable cost.

Hydraulic motion has benefits over electric or pneumatic systems, especially when high-speed linear travel is involved, heavy loads must be moved or held in place, or when very precise and smooth position or pressure control is required. Hydraulic actuators have a number of advantages including the fact that they produce less heat and electrical interference at the machine than do electric actuators. Particularly with high-performance hydraulic systems, they let you build machines at considerable savings compared to machines employing purely electrical or mechanical motion.

Designing a hydraulic control system involves several design considerations and tradeoffs. Key among them are selecting the proper system components and setting up the motion controller with the proper control algorithm. Compromises can be made when designing the hydraulic circuit, but if there are deficiencies that would lead to sub-optimal performance, even the best electro-hydraulic motion controllers can’t compensate for them. A motion controller executing closed-loop control can’t make the system move faster or accelerate faster than an open-loop control, but it can make the system move more accurately and reliably.

Here are some helpful tips for component selection and sizing in a typical high-performance hydraulic motion system.

Pumps

Pumps supply the oil under pressure required to move the cylinder pistons. Usually only one pump is required to move one or more positioners, so it should only be sized for the average oil supply required to complete a machine cycle. This assumes that accumulators are properly sized and precharged so they can store the oil under pressure when the system is not moving. Undersized pumps result in systems that can’t move at desired speeds or decelerate to a target position quickly. Oversized pumps are wasteful as they cost more and require bypassing oil to the storage tank when the system isn’t moving. Sizing pumps for average power requirements is an advantage for hydraulics, compared to electric motors, which must be sized to meet peak power requirements.

Cylinders

Just as the right size hydraulic pump is critical, so are correctly sized hydraulic cylinders. Increasing the size of a cylinder increases the natural frequency, or stiffness, of the system and allows it to accelerate faster, at the cost of requiring larger valves and pumps than smaller cylinders used in non-speed-critical applications.

Designers sometimes intend to increase piston rod speed by specifying a cylinder with a smaller bore, based on the assumption that for a given amount of oil flow, a smaller cylinder will produce quicker accelerations and higher velocities. However, this may only work for light loads up to around 100 lb. For actuators moving moderate to heavy masses from several hundred up to a thousand pounds, acceleration, velocity, and deceleration are limited by the available force, not by oil flow. Because cylinder bore determines the force that it can produce, if the bore is too small, the cylinder may be incapable of reaching the desired speeds or cycle times the applications requires.

Accumulators

An accumulator is an energy storage device, a reservoir for hydraulic pressure. Accumulators store energy when the system energy demands are less than average, and transmit energy back into the system to satisfy peak demands. For best results, use an accumulator of adequate size and place it close to the valve. Oversized pumps do not replace accumulators. Use of a correctly sized accumulator allows the hydraulic pump to be sized for just the average power required by the system, saving cost and energy.

Another advantage of storing energy in accumulators is that they can support faster accelerations than pumps used directly to build pressure, because pumps take time to build pressure. If there is more than one actuator (valve/cylinder combination) in the system, consider peak loading when sizing the accumulator. If it appears that there will be a problem with maintaining constant supply pressure throughout a multi-actuator system, consider using multiple accumulators, placed close to where the energy is used.

Plumbing

Use solid piping rather than hose between the valve and the cylinder, because hoses expand and contract and change shape, impacting system controllability. Keep pipes as short and straight as possible, as pressure drops occur in bends. Place the valves either on the cylinders or as close as possible to the cylinders to keep the volume of oil between the valve and cylinder as small as possible. This helps keep the system’s natural frequency as high as possible.

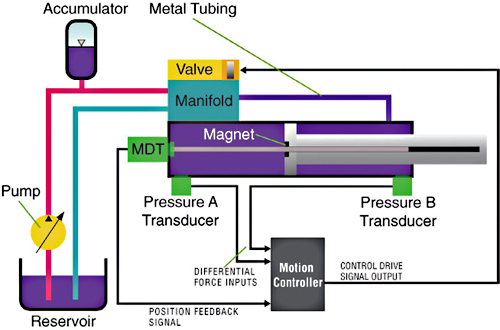

A typical hydraulic circuit showing all of the major components along with the electro-hydraulic motion controller.

Valves

Linear valves with zero overlap are the best choice. They can be either servo valves or servo-quality proportional valves. Proportional valves avoid fluid surges that other valves, such as on/off or “bang-bang” valves, can cause, reducing the potential for fluid leaks and extending machine life. Choose valves with response times and flow rates that match the application, avoiding grossly over-sizing the valves. A valve that uses most of its range is generally easier to control.

Zero overlap valves are preferable because there’s no “dead band” of zero fluid flow between active control ranges, which are ranges that increase or decrease hydraulic pressure. Valves with overlap may be better for manually controlled systems, but because it’s difficult for a motion controller to control the system when the valve is in the dead band region, they’re not good for high-performance, high-precision automated control.

Another valve that can cause control problems is the counterbalance valve, sometimes used as a type of automatic safety valve to keep loads from dropping when there is a loss of hydraulic pressure. However, in systems controlled by a motion controller, these valves often create problems when they act in opposition to the action of the servo valve. A better solution is to use solenoid-activated blocking valves that can be controlled by the motion controller along with the servo valves.

Pressure Transducers

In hydraulic applications that require exerting a precise pressure, automated pressure monitoring is a necessity. Pressure relief valves can play a role in preventing unsafe conditions by ensuring that hydraulic pressure doesn’t rise above a nominal value. However, they make poor pressure or force controllers. A relief valve only limits pressure or force, and on only one side of the piston. But using pressure transducers enables precise control of applied pressure or force.

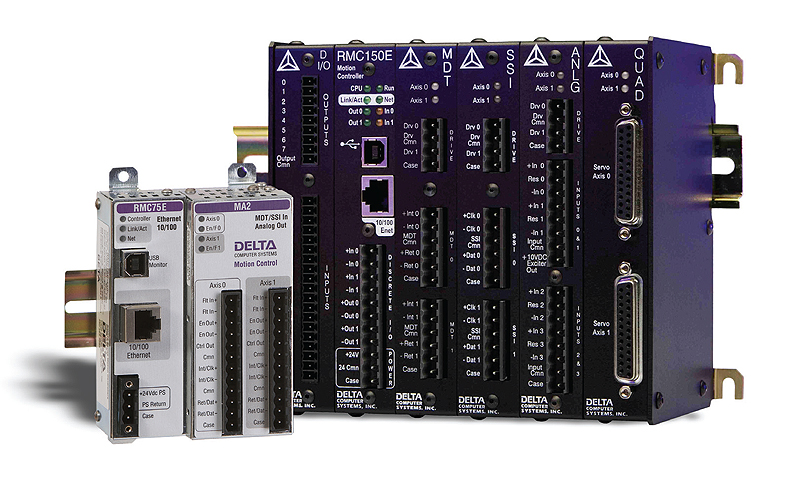

Motion controllers, such as the RMC75 and RMC150 controllers by Delta Computer Systems, provide direct interfaces to transducers and proportional valves to simplify system integration.

Pressure transducers are commonly applied in pairs for force control applications. Separate sensors monitor the pressure on each side of the piston, with the resulting force calculated according to the equation:

Force = PPE x APE – POE x AOE

Where:

PPE = pressure on the powered side of the piston

APE = the area of the powered end of the piston

POE = pressure on the opposing end of the piston

AOE = the area of the opposing end of the piston.

In some applications where pressure changes quickly, the pressure transducers need to respond quickly. Examine the specifications of different transducers to ensure that they can respond quickly enough for the application. In addition, where pressure transducers are mounted in a system is also critical. It’s best to mount transducers as close as possible to the points of interest on the cylinder—the fluid flow is less turbulent in the larger areas of the cylinder, and there are no propagation delays as would be caused if pressure were measured in the tubing outside the cylinder.

Position Transducers

The best sensors for position feedback to the motion controller are magnetostrictive linear displacement transducers (MLDTs), which are typically mounted in the cylinders. MLDTs are best because they use moving magnets that don’t come in contact with the sensor tube, avoiding mechanical wear, and they provide an absolute position readout, requiring no homing step before beginning to work with the position information from the MLDT. Advances in MLDT technology have led to resolutions down to 1 μm, with fast signal processing of up to 1.5 MHz.

Motion Controller

A programmable motion controller designed to precisely control applied force and transition smoothly from position control to force control is an essential part of an electric hydraulic control system. Machines can be adapted automatically to deal with different material consistencies and the effects of differing environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity. Also, more flexible production results from theability to easily change a ‘recipe’ that changes positions and forces specified during the machine cycle. Machine downtime for production changeovers can be significantly reduced. Further, target positions and forces can be changed “on-the-fly,” allowing more flexibility in making more challenging parts.

More consistent, smooth motion also results in less wasted or rejected parts, and ensures consistent production output quality from different machine operators with widely varying skill levels. By automatically coordinating the motion of multiple axes, you can scale machine performance, improving productivity at the high end, while facilitating troubleshooting at slower speeds.

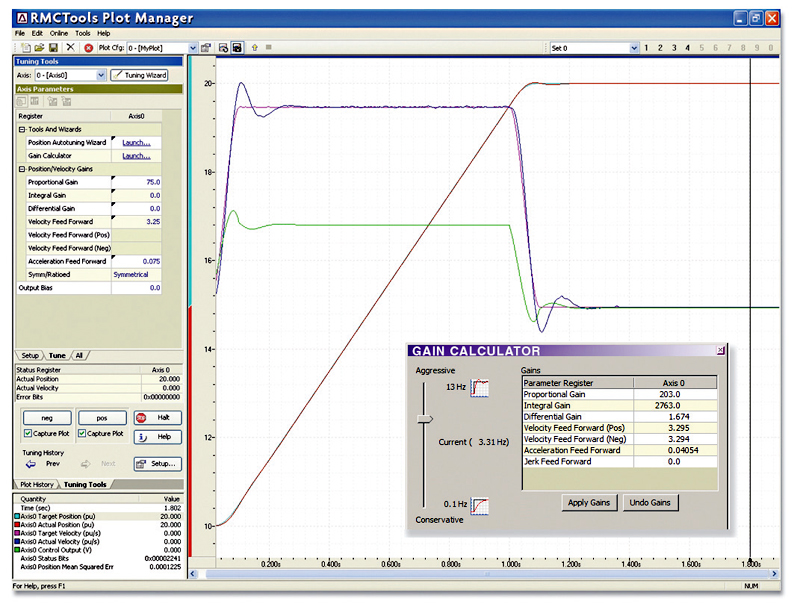

A motion plot produced by Delta Computer Systems RMCTools Plot Manager software. The red curve indicates axis position, the blue curve axis velocity, and the green is the drive level being provided to the proportional valve.

Look for motion controllers that have the right connections and capabilities for the application. For instance, some motion controllers may have direct interfaces to the system’s position and pressure transducers. If the application requires the controller to transition from control based on position information to control based on pressure, the motion controller must be able to interface to position and pressure sensors. Motion controllers that provide direct transducer interfaces may offer the best cost/performance by eliminating the need for separate interfacing modules that can create performance bottlenecks. Also look for a motion controller that provides analog control signals to drive proportional valves.

Fieldbus Interfaces

Selecting motion controllers that can interface directly to the system’s PLC or human-machine interface (HMI) makes the system simpler to design and lowers hardware costs. Likewise, a controller that interfaces to a standard fieldbus such as PROFIBUS or EtherNet/IP frees you from being locked into a single vendor’s control system offerings.

For simpler applications, not requiring megabit data transfer rates, look for motion controllers that have serial interfaces that support standards such as RS-232, RS-422, and RS-485, with communication protocols that can talk to popular PLCs/HMIs, such as Allen-Bradley.

Multi-axis Control

System costs can be kept down if the motion controller is capable of managing multiple axes. Look for controllers that offer different types of multi-axis control including synchronization, which involves controlling multiple axes such that they move in lock step; gearing, where the relative motion of multiple axes is tightly controlled, but the ratio of control can be changed as the system operates; or camming, where the gear ratio between a slave and master axis is expressed as a nonlinear equation.

Powerful Motion Instructions

New motion controllers also support powerful instructions that can make program-ming easier. For example, hydraulic press applications benefit from controllers that support built-in commands for complex motion profiles such as curves. The controllers interpolate data provided by the user or a host controller. Curves may be programmed to perform either time-based motion, where the curve defines the position of the axis at certain times, or master-based motion, where the curve defines the position of the axis based on a master input, such as the position of another axis.

In typical machine operation, a controlling PLC programs the motion controller by writing sequences of motion commands called “steps” into the controller. Some controller manufacturers and third-party control software companies offer tools that support graphical programming of control profiles.

Discuss this on the Engineering Exchange:

Delta Computer Systems, Inc.

www.deltamotion.com

::Design World::

We need Electro-Hydraulic Motion Control Systems. cylinder active 0-60 mm, double active. Pressure form 10KN to 100KN. Accuracy 2% for position and pressure. Pl, sent for us technical data information prices. We use to for new tablet press machine in pharmaceutical.